Navigating the complexities of UK law can be daunting, particularly when dealing with matters of personal responsibility and future planning. Power of Attorney, a legal instrument granting another person authority to act on your behalf, is a crucial tool for ensuring your wishes are respected, even if you become incapacitated. This guide explores the intricacies of Lasting Powers of Attorney (LPAs) and Enduring Powers of Attorney (EPAs) in the UK, providing a clear understanding of their differences, creation, management, and potential legal ramifications.

We will delve into the specific requirements for establishing each type of power of attorney, detailing the responsibilities of both the donor (the person granting the power) and the attorney (the person appointed to act). Furthermore, we will examine the safeguards in place to protect vulnerable individuals from potential exploitation and Artikel the steps involved in challenging or terminating an existing power of attorney. This comprehensive overview aims to equip readers with the knowledge necessary to make informed decisions about their future care and financial affairs.

Types of Power of Attorney in UK Law

Power of Attorney (POA) in the UK grants another person (your attorney) the authority to make decisions on your behalf. This is particularly crucial if you lose the capacity to manage your affairs due to illness or incapacity. There are two main types of POA, each with distinct features and legal requirements.

Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) and Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA)

The Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) is the most common and current type of POA in England and Wales. It replaced the Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA) in 2007. The key difference lies in when the power of attorney takes effect. An LPA only comes into effect when you lose mental capacity, while an EPA could be activated immediately upon signing or later, if you lost capacity. EPAs are now largely obsolete, although some still exist. It’s vital to understand the distinctions to ensure your affairs are managed according to your wishes.

Legal Requirements for Creating a Lasting Power of Attorney

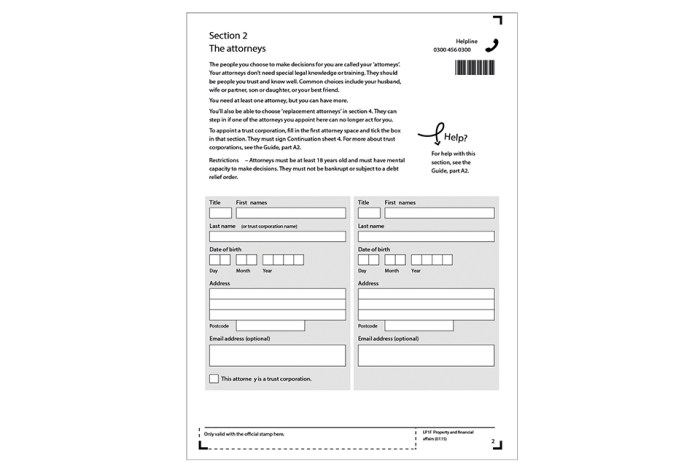

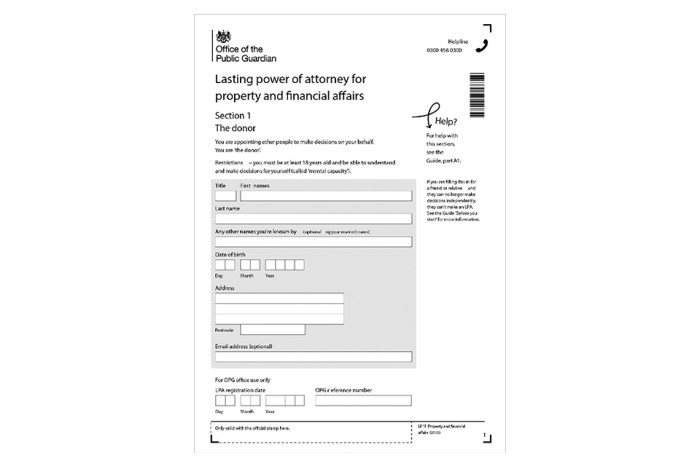

Creating an LPA involves several legal steps to ensure its validity and enforceability. You must be over 18 and have the mental capacity to understand the document and its implications. The LPA must be completed using the official government forms, witnessed correctly, and registered with the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG). Failure to adhere to these requirements can invalidate the LPA. There are specific requirements for the attorney, including their identity verification. The document should clearly state the scope of the attorney’s powers, ensuring they align with your wishes.

Types of Lasting Power of Attorney

There are two types of LPAs: one for property and financial affairs, and another for health and welfare.

Property and Financial Affairs LPA

This LPA grants your attorney the power to manage your financial affairs, including accessing your bank accounts, paying bills, selling property, and managing investments. This is appropriate if you anticipate needing help with managing your finances due to age, illness, or any other reason that might impair your decision-making abilities. For example, if you were to experience a debilitating stroke and become unable to handle your finances, this LPA would allow your designated attorney to take over.

Health and Welfare LPA

This LPA allows your attorney to make decisions about your health and welfare, including where you live, what medical treatment you receive, and your daily care. This is particularly relevant if you anticipate needing help making decisions about your care in the future. For instance, if you develop dementia and are no longer able to communicate your wishes regarding your medical treatment, this LPA allows your attorney to act on your behalf based on your previously expressed preferences or what they believe to be in your best interests.

Key Distinctions Between LPAs and EPAs

| Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) | Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA) |

|---|---|

| Comes into effect when you lose mental capacity. | Could be activated immediately or upon loss of mental capacity. |

| Requires registration with the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG). | Does not require registration. |

| Two types: Property & Financial Affairs, and Health & Welfare. | Covers both property and financial affairs and health and welfare decisions. |

| More robust legal protection. | Less robust legal protection and largely obsolete. |

Powers and Responsibilities of an Attorney

An attorney acting under a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) holds significant responsibility for managing the affairs of the donor (the person granting the power). Understanding the scope of their authority, and the potential legal consequences of exceeding it, is crucial for both the attorney and the donor. This section details the powers and limitations inherent in both Property and Financial Affairs LPAs and Health and Welfare LPAs.

Limits and Boundaries of an Attorney’s Authority

The attorney’s authority is strictly defined by the terms of the LPA itself. They can only act within the powers explicitly granted by the donor. Any actions taken outside these parameters are considered to be acting outside their authority, which can have significant legal repercussions. The LPA should clearly specify the attorney’s powers, including any restrictions or limitations. For example, an LPA might grant the attorney the power to manage bank accounts but restrict their ability to make significant investments without consulting another designated person. The donor can also specify the types of decisions that require the consent of a second person, ensuring a safeguard against misuse of authority. Importantly, the attorney has a legal and ethical duty to act in the best interests of the donor at all times.

Legal Implications of an Attorney Exceeding Their Powers

If an attorney acts outside the scope of their LPA, their actions can be challenged in court. This could lead to the attorney being personally liable for any losses incurred, and potentially facing legal action from the donor or their beneficiaries. For instance, if an attorney uses the donor’s funds for their own benefit, they could be prosecuted for fraud or theft. Similarly, if an attorney makes decisions regarding the donor’s health and welfare that are clearly against the donor’s best interests and not authorized in the LPA, they could face legal challenges and sanctions. The court will examine the actions of the attorney against the specific terms of the LPA and the donor’s wishes, as evidenced in the document and any supporting evidence.

Comparison of Powers Granted Under Property and Financial Affairs LPAs and Health and Welfare LPAs

Property and Financial Affairs LPAs and Health and Welfare LPAs grant distinct powers. Property and Financial Affairs LPAs allow the attorney to manage the donor’s finances, property, and affairs. This includes managing bank accounts, paying bills, selling property, and making investments. Health and Welfare LPAs, on the other hand, allow the attorney to make decisions regarding the donor’s health, personal welfare, and lifestyle. This can include decisions about medical treatment, accommodation, and daily routines. Crucially, while a Property and Financial Affairs LPA focuses on the donor’s assets, a Health and Welfare LPA prioritizes the donor’s well-being and quality of life. It is important to note that these LPAs are separate and distinct documents; one does not automatically grant the powers of the other.

Powers, Limitations, and Responsibilities of an Attorney

| Power | Property and Financial Affairs LPA | Health and Welfare LPA |

|---|---|---|

| Manage Finances | Can manage bank accounts, pay bills, invest funds, sell property, etc. Limited by specific instructions within the LPA. | Generally, no direct power over finances, unless explicitly stated in the LPA. |

| Make Healthcare Decisions | No power unless explicitly stated within the LPA. | Can make decisions about medical treatment, care, and living arrangements. Must act in the donor’s best interests and in accordance with the LPA’s terms. |

| Manage Property | Can manage, sell, or rent property. Limited by specific instructions within the LPA. | Can make decisions regarding the donor’s place of residence, but financial implications are usually handled by a separate Property and Financial Affairs LPA. |

| Limitations | Bound by the specific instructions within the LPA. Must act in the donor’s best interests. Cannot act in their own self-interest. | Bound by the specific instructions within the LPA. Must act in the donor’s best interests. Cannot make decisions that are contrary to the donor’s known wishes. |

| Responsibilities | Keep accurate records of all financial transactions. Act honestly and transparently. Inform the donor (where possible) of significant decisions. | Keep accurate records of decisions made. Consult with healthcare professionals where necessary. Act honestly and transparently. Inform the donor (where possible) of significant decisions. |

Challenging or Ending a Power of Attorney

A Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) grants significant authority to an attorney, and it’s crucial to understand the mechanisms available to challenge or terminate its operation if concerns arise. This section details the grounds for challenging a validly executed LPA, the procedure for ending one, and examples of court intervention.

Grounds for Challenging a Validly Executed LPA

A validly executed LPA can still be challenged under specific circumstances. These challenges typically center around allegations of the attorney acting improperly, or that the donor lacked the necessary capacity when creating the LPA. This could involve claims of undue influence, fraud, or the attorney acting against the donor’s best interests. The court will carefully scrutinise the circumstances surrounding the creation and execution of the LPA, examining evidence presented by all parties involved.

Procedure for Ending a Power of Attorney

Ending a power of attorney can occur through several methods. The donor, if they still possess the necessary mental capacity, can revoke the LPA by notifying the attorney and the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG). Alternatively, the attorney may choose to relinquish their role voluntarily. In cases of concern about the attorney’s conduct or the donor’s well-being, an application can be made to the Court of Protection to revoke or modify the LPA. This process requires formal legal action and evidence supporting the application.

Examples of Court Intervention to Revoke or Modify an LPA

Courts will intervene in situations where there is evidence of the attorney misusing their powers, acting against the donor’s best interests, or where the donor’s circumstances have significantly changed rendering the LPA inappropriate. For example, if an attorney is found to be misappropriating funds from the donor’s account, or consistently ignoring the donor’s wishes, the court may intervene to revoke the LPA and appoint a new attorney or place the donor’s affairs under the control of the OPG. Another example might be a situation where the donor’s health deteriorates to the point where their previously expressed wishes are no longer applicable. The court might then modify the LPA to better reflect the donor’s current needs.

Applying to the Court of Protection to Challenge or End an LPA

Applying to the Court of Protection is a formal legal process. The following steps Artikel the procedure:

- Gather evidence: Compile all relevant documentation, including the LPA itself, evidence of the attorney’s actions, medical reports regarding the donor’s capacity (if relevant), and any other supporting evidence.

- Seek legal advice: Consult with a solicitor specialising in Court of Protection matters. They will advise on the strength of your case and assist with preparing the necessary paperwork.

- Prepare the application: The application must be made in the correct format and include all necessary details, such as the donor’s information, the LPA details, and the grounds for the challenge.

- File the application: Submit the application and supporting documents to the Court of Protection.

- Attend court hearings: Be prepared to attend hearings where the court will consider the evidence and make a determination.

- Court Order: The court will issue an order either revoking, modifying, or upholding the LPA based on the evidence presented.

Protecting Vulnerable Individuals

The creation and implementation of a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) aims to safeguard an individual’s autonomy and well-being, particularly as they age or experience declining health. However, the inherent vulnerability of individuals granting LPAs necessitates robust safeguards to prevent exploitation and ensure their best interests are protected. These safeguards encompass various legal mechanisms, oversight bodies, and preventative measures designed to identify and address potential abuse.

The potential for abuse underscores the critical importance of understanding the protections in place. This section details the safeguards designed to protect vulnerable individuals from exploitation, highlighting the role of the Office of the Public Guardian and providing practical examples of potential abuse and preventative strategies.

Safeguards Against Exploitation Under an LPA

Several safeguards are built into the LPA system to mitigate the risk of exploitation. These include the requirement for the donor to have capacity when creating the LPA, the need for the attorney to act in the donor’s best interests, and the ability to challenge or revoke the LPA if necessary. The Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) plays a crucial role in monitoring LPAs and investigating potential abuse. Furthermore, the LPA itself can be structured to limit the attorney’s powers, providing additional layers of protection. For example, an LPA can specify that certain actions require the consent of another person or that the attorney must regularly report to the donor or a trusted individual.

The Role of the Office of the Public Guardian

The Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) is a government body responsible for overseeing LPAs in England and Wales. Their role encompasses registering LPAs, providing guidance and information to donors and attorneys, and investigating allegations of abuse or mismanagement of LPAs. The OPG can investigate complaints, take action against attorneys who are acting improperly, and even appoint a deputy to manage the donor’s affairs if the attorney is unable or unwilling to do so appropriately. The OPG’s powers allow for intervention and rectification of situations where a donor’s best interests are not being served.

Examples of Potential Abuses of Power and Prevention

Potential abuses of power under an LPA can range from financial mismanagement and theft to neglect and emotional abuse. For instance, an attorney might use the donor’s funds for their own benefit, fail to provide adequate care for the donor, or isolate the donor from family and friends. Prevention strategies include choosing a trustworthy and responsible attorney, carefully drafting the LPA to specify powers and limitations, regularly reviewing the LPA’s implementation, and maintaining open communication between the donor, attorney, and any other relevant parties. Independent financial advice for the donor can also provide an extra layer of protection against financial exploitation. Furthermore, appointing a second attorney can create a system of checks and balances, reducing the risk of unilateral decisions.

Warning Signs of Potential Abuse of an LPA

It is crucial to be aware of warning signs that might indicate potential abuse. Early detection can allow for timely intervention and prevent further harm.

- Unexplained changes in the donor’s financial situation, such as unusual withdrawals or transfers of funds.

- A significant deterioration in the donor’s living conditions or personal care.

- The donor expressing concerns about the attorney’s actions or decisions.

- The attorney restricting the donor’s contact with family and friends.

- Lack of transparency or accountability regarding the management of the donor’s affairs.

- Suspicious activity or transactions related to the donor’s property or assets.

- The attorney refusing to provide information or cooperate with inquiries.

Legal Consequences of Non-Compliance

Acting as an attorney under a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) carries significant responsibilities. Failure to meet these responsibilities can lead to serious legal consequences, impacting both the attorney and the donor (the person granting the power). Understanding these potential repercussions is crucial for anyone considering accepting the role of attorney.

Penalties for Breach of Duty

An attorney has a legal and ethical duty to act in the best interests of the donor. Breaching this duty can result in a range of penalties, depending on the severity and nature of the breach. These penalties can include financial sanctions, court orders requiring the attorney to rectify their actions, and even criminal prosecution in serious cases. The Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) oversees LPAs and has the power to investigate complaints and take appropriate action.

Examples of Legal Action Resulting from Non-Compliance

Several cases illustrate the potential legal consequences of non-compliance. For instance, a case might involve an attorney misusing funds from the donor’s account for personal gain. This could lead to civil action for breach of trust, potentially resulting in financial penalties and a court order to repay misappropriated funds. Another scenario could involve an attorney neglecting the donor’s welfare, leading to a court application to remove the attorney and appoint a replacement. In extreme cases, criminal charges, such as fraud or theft, could be brought against an attorney who has acted dishonestly or illegally. The specific outcome depends on the facts of each case and the evidence presented.

Categorization of Legal Consequences

| Severity | Type of Penalty | Potential Consequences | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minor | Formal Warning/Reprimand | OPG issues a formal warning or reprimand, documenting the breach. | Minor administrative errors, such as late filing of reports. |

| Moderate | Financial Penalties/Court Orders | Financial penalties imposed for misuse of funds or breaches of trust; court orders to rectify actions. | Misuse of a small portion of the donor’s funds for personal expenses. |

| Serious | Removal as Attorney/Criminal Prosecution | The attorney is removed from their position, and a replacement is appointed; criminal charges are brought. | Fraudulent activity involving significant sums of money or serious neglect of the donor’s care. |

| Severe | Imprisonment/Significant Financial Penalties | Imprisonment and substantial financial penalties for serious criminal offences. | Theft or embezzlement of large sums of the donor’s money. |

Epilogue

Effective planning for the future is paramount, and understanding the UK’s power of attorney laws is a critical step in safeguarding your interests and those of your loved ones. By carefully considering the different types of LPAs, understanding the responsibilities involved, and being aware of the potential legal consequences of non-compliance, individuals can ensure a smooth and legally sound process for managing their affairs. This guide has provided a framework for navigating this complex area of law, empowering you to make informed choices and protect your future well-being.

FAQ Summary

What happens if my attorney dies before me?

If your attorney dies before you, the LPA becomes ineffective. You will need to create a new LPA with a new attorney.

Can I revoke my LPA after it’s been registered?

Yes, you can revoke your LPA at any time, provided you have the mental capacity to do so. You’ll need to complete a revocation form and submit it to the Office of the Public Guardian.

Can I appoint more than one attorney?

Yes, you can appoint multiple attorneys, either jointly (both must agree on decisions) or severally (each can act independently).

What if I don’t have anyone suitable to act as my attorney?

If you don’t have a suitable person to act as your attorney, you can consider using a professional deputy appointed by the Court of Protection. This is a more formal and costly process.